This writing is dedicated to my Father, Guido Joseph Piccinino

October 6, 1909 – June 9, 2000

and my Mother, Millie Piccinino

June 22, 1917 – Dec.1, 1994

Joe’s Food Market

4517 Baltimore Ave.

Philadelphia, PA 19143

EVergreen 6-4190

In the late 1960’s, one of my father’s customers of his store, a U of P, Art History Prof., gave him a xerox copy of a page from “Vasari’s Lives of the Artists”. In trying to find a copy of that particular book I learned the following information.

This is a copy a Family Crest given to me by Lucio Piccinino of Milan whom I communicated with through email. This was his father’s.

Richard J. Piccinino

Rpiccinino@cox.net

June 16, 2000

NICCOLO PICCININO

and his sons FRANCESCO AND JACOPO

Niccolo Piccinino was born in 1380 as a son of a butcher. Niccolo was small in stature, but a mighty warrior. He rose through the military ranks under Braccio da Matrone, the most celebrated and loved Condottiere (Soldier of Fortune) of Italy. Both men were born in the city of Perugia (Perusia), in the Umbria region of Italy. In Perugia, there exists today, the Piazza Piccinino, in honor of Niccolo.

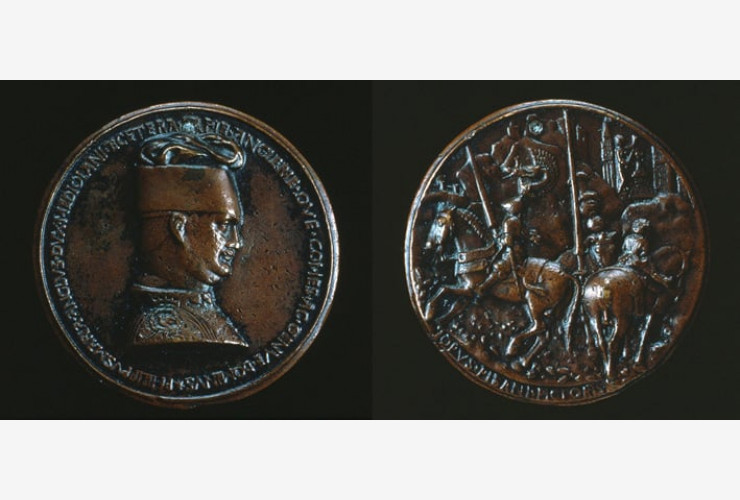

There is a medal of Niccolo, that has the “she-griffin of Perusia” (Perugia) suckling her two infants, Niccolo and Braccio.

Medal of Niccolo Piccinino

This medal was created by Antonio Pisanello, who was also know as Pisanello

Front of Medal:

Bust to left in plate-armour, in tall cap; on the shoulder piece, Milanese armourer’s mark AA crowned. Around (in Latin): NICOLAVS PICININVS VICEOMES MARCHIO CAPITANEVS MAX(imus) AC MARS ALTER

Reverse of Medal:

The she griffin of Perusia (PERVSIA on collar) suckling two infants, the condottiere Braccio da Montrone (BRACCIVS) and Piccinino (N. PICININVS)

The size is about 90 mm and was made around 1441. The design of the reverse was suggested by the Roman wolf and twins. Piccinino bore the name of Visconti from his adoption by the Duke of Milan (Filippo Marie Visconti) in 1439 to his adoption by the King of Naples in 1441 or 1442.

Collection: Signol (sale Paris, April 1, 1878, lot 155)

One of the first commissions of Niccolo Piccinino, was given by Giovanni de Medici, of Florence, to induce the Lord of Faenza from going into Romagna. In this battle, Count Odo, son of Braccio da Matrone, was slain and Niccolo was taken prisoner. In his captivity, Niccolo, with his charming personality, not only became true friends with the Lord of Faenza and his mother, but he also was able to conclude a peaceful settlement in the dispute for Florence.

Niccolo then was taken under the wings of Duke Filippo Marie Visconti, sole Lord of Lombard, Duke of Milan, in about 1412, as his most capable condottiere. Duke Filippo was an interesting character. He was extremely overweight and always needed a servant near by to help him up. He banished his first wife because he believed that she committed adultery. His second wife, he had exiled because on their wedding night, he heard a dog howl, and he believed that to be a sign that she was possessed. Despite these things, the Duke had a keen sense of ruling over Milan and dealing with his neighboring states, the Church and for protecting his own interests.

Duke Fillippo was one of the first to create the use of Tarot cards. The Visconti-Sforza tarot is used collectively to refer to incomplete sets of approximately 15 decks from the middle of the 15th century, now located in various museums, libraries, and private collections around the world. No complete deck has survived; rather, some collections boast a few face cards, while some consist of a single card. They are the oldest surviving tarot cards and date back to a period when tarot was still called Trionfi (“triumphs”[1] i.e. trump) cards, and used for everyday playing.[2][3] They were commissioned by Filippo Maria Visconti, Duke of Milan, and by his successor and son-in-law Francesco Sforza. They had a significant impact on the visual composition, card numbering and interpretation of modern decks.[4]

During one battle, Niccolo Piccinino was cut off from the rest of his troops behind the enemy’s line. He made a daring escape, placing himself in a sack. His long time loyal servant, a big strong dutchman, carried him in this sack, pass the enemy and back to his troops. There is a Tarot card depicting this that I need to relocate.

By 1433, Italy was then divided into two fractions, the “BRACCESCHI”, under Niccolo Piccinino and Niccolas Fortebracio, the other “SFORZESCI” under Count Francesco Sforza. The condottiere, Count Sforza, was from Naples, which was first ruled by Rene of Anjou, son of Giovanna, Queen of Naples. Later, Naples was taken by Alfonso.

Duke Filippo Marie Visconti, of Milan continually promised Niccolo Piccinino, land to rule and also his daughter’s hand in marriage. This would have given Niccolo the right to succeed Filippo as ruler of Milan. Because Filippo needed Naples’s support, he started favoring Count Sforza, who was Niccolo Piccinino’s natural enemy. Filippo eventually gave his daughter to Sforza, duping Niccolo.

While in a battle for Naples and the Church, Niccolo was called to Milan, thinking Filippo was going to repay him for his years of service and loyalty, he left a certain victory at hand to his son Francesco to finish. While in route, Niccolo learned of Filippo’s trickery, and that his son had been captured. Niccolo then died of grief in 1445 at the age of 64.

Sforza, after the death of Filippo Marie Visconti, rose to the leader of all of Milan. Sforza appointed Jacopo Piccinino, Niccolo’s son, to conduct his forces to protect Milan, despite their ancient family feud. Over the years Jacopo attained the highest reputation as the “First General of Italy” and earned respect and admiration throughout the land. Alfonso, King of Naples, fearing all external opposition to his thrown, induced Francesco Sforza for his help in this matter. Sforza, called for Jacopo Piccinino to return to Milan, where he was received by both the people and the nobility with such great honors. They shouted with joy and respect “The Bracceschi, The Bracceschi”, which is what Alfonso and Sforza feared the most. Disguising his plans, Sforza gave Jacopo his daughter, Drusina, in marriage. He also gave him 100,000 florins and the title of Captain.

With this same pretense, Jacopo was also summoned to Naples, where again, the people and nobility held celebration in his honor that lasted for three days in honor of Jacopo Piccinino. After the banquet with the King, both Francesco and Jacopo were then imprisoned and then shortly after, put to their deaths in the Castel Nuovo.

THE BATTLE OF THE STANDARDS

The Da Vinci Connection

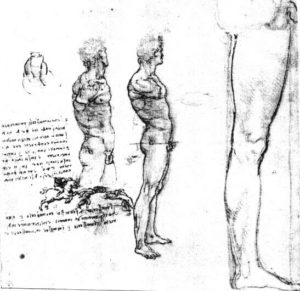

The story of Niccolo Piccinino has been embedded in eternity by Leonardo da Vinci. The grand council of Florence initiated an art project as a competition between their two great sons, Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci. They wanted Florence to be the new Athens of the world.

Michelangelo, choose for his project the “Battle of Cascina”, which having been called to Rome, he had to abandoned. Leonardo choose “The Battle of Anghiari”. This battle was actually a minor one that lasted for only four hours, and in it, only one person was killed, and by being trampled by a horse. This battle was also lost by Niccolo Piccinino and his son Francesco. The actual painting is in question to its existence and has only recently been seen through Da Vinci’s Madrid Notebooks. Attempts are now being made to x ray the wall to “see” the actual painting at the Palazzo Vecchio. One my greatest joys was to be in Florence and see that wall.

Leonardo began drawing the “Battle of Anghiari” in October of 1503, in the Sala del Gran Consigglio of the Palazzo Vecchio. This is the Grand Council Hall of Florence. The painting was still admired up to the year 1513, when a wall was built around it for protection. It was Vasari who finally destroyed this work by painting over the fresco with his own work.

The grisaille of Rubens, “Battle of Anghiari” is what best illustrates Leonardo da Vinci’s “Battle of the Standards”. It having been destroyed fifty years before he could have seen the original, had to go on a engraving of Lorenzo Zacchia.

The details of this masterpiece is colorfully described by Giorgio Vasari in his book “Vasari’s Lives of the Artists”, on Page 194. “…All men who delighted in the arts, in fact, all the people of Florence, were anxious to have some great public work by Leonardo, that the commonwealth might have the glory and the city the ornament imparted by his genius, grace, and judgement. It was decreed that Leonardo should paint something for the newly completed Hall of the Grand Council. He began a caricature of an episode in the story of NICCOLO PICCININO, in which he depicted a group of horseman fighting around a standard, a masterly composition. It is an odd thing to see that not only do the men show rage, disdain, and the desire for revenge, but the horses, too, are attacking each other with their teeth, and fight no less fiercely than the knights.

One of the combatants has seized the standard with both hands and strives to tear it with main force from the hand of four others. An old soldier in a red cap has also seized the standard with one hand and is raising his scimitar in the other, uttering cries of rage as he deals a blow to sever the hands of two of his opponents. Under the feet of the two horses two men, dagger down with all his might to the throat of his enemy. It is scarcely possible to do justice to the skill of this drawing, the beauty of the details of the helmets, crests, and other ornaments or to the wonderful mastery which the artist shows in the form and movements of the horses. Their muscular development, the animation of their action, and their exquisite beauty are rendered with the utmost fidelity….”

It has been said that Leonardo invented a scaffolding for working on this caricature, which was raised by drawing it together, and lowered by making it wider. Da Vinci loved to experiment with different techniques, but this fresco had a disastrous failure. It was his intention to paint this picture in oil on the wall, but he made his grounds so that the paint began to sink into it very soon after he put it on, and so he abandoned the whole project. This failure may also have been caused by an extremely cold winter that year and that Leonardo did not have enough money for all the linseed oil needed.

The creation of the “Battle of the Standards” can be seen in a TV documentary called “The Season of the Giants”, of which there is also a book, with this same title. It tells the story of that great period of time, “The Renaissance”, when Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael lived and worked in Italy, and how religion, art and politics were all woven together.

My favorite part of that movie is when da Vinci’s apprentice is reading from Machiavelli’s account of the Battle of Anghiari, and hearing the name “Niccolo Piccinino” read aloud.

Niccolo Piccinino died in 1444, that would be 61 years before da Vinci’s work. Any likeness to him may have been seen through the artist Antonio Pisanello’s medal of Niccolo. Pisanello was a renowned painter and medalist of the early Renaissance. Pisanello, a contemporary of Niccolo Piccinino, was banished from the Venetian territory because he was a member of the retinue of Giovanni Gonzaga and Niccolo Piccinino during the siege of Verona on Nov. 17, 1439. This may also be the reason why he is sometimes refered to as, Vittore Pisano.

Pisanello was one of a few artists allowed to portrait Duke Filippo Marie Visconti. Mostly because of the way that he soften Filippo’s appearance.

In “Vasari’s Lives of the Artists”, Vol. 2, Page 20, there is an excerpt of a letter from Monsignor Giovio to Duke Cosimo which talks about the medal of Niccolo Piccinino. “….This same Pisano (PISANELLO) made a large number of portraits of the prominent men of his day in cast medals, and of others whose portraits have since been painted from them. Monsignor Giovio in a letter in the vernacular written to Duke Cosimo, which has been printed with many others, says these words in speaking of Vittore Pisano; He was also most excellent in making bas-reliefs, which are considered most difficult by artists, because they are midway between the flat level of painting and the full relief of sculpture and many much admired medals of great princes by his hand may be seen, made in the large size of the same dimensions as the reverse which Il Guidi has sent me of the armed horse. Among these I have one of King Alfonso with a shock of hair, the reverse being a captain’s helmet; that of Pope Martin, with the Colonna arms on the reverse; one of the Sultan Mahomet who took Constantinople, with himself on horseback in Turkish costume and a scimitar in his hand; Sigismondo Malatesta, the reverse being Madonna Isotte of Rimini; and NICCOLO PICCININO with an oblong cap on his head, the reverse of Il Guidi….”

In this letter the description of the reverse of the medal is not the same as the medal that is pictured here. Perhaps there may be an other medal of Nicciolo Piccinino.

Another fine source of information on Niccolo Piccinino comes from Jocob Burkhardt’s “The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy”, pages 13 – 14, The State as a Work of Art.

“…Aeneas Sylvius wrote about this time (Milan 1447 – 1450) ” in our change- loving Italy, where nothing stands firm, and where no ancient dynasty exists, a servant can easily become a king.” One man in particular, who styled himself “the man of fortune,” filled the imagination of the whole country: GIACOMO PICCININO (JACOPO), son of NICCOLO PICCININO. It was a burning question of the day if he, too, would succeed in founding a princely house. The greater states had an obvious interest in hindering it, and even Francesco Sforza thought it would be all the better if the lists of self-made sovereigns were not enlarged. But the troops and captains sent against him, at the time, for instance, when he was AIMING AT THE LORDSHIP OF SIENA, recognized their interest in supporting him: “If we were all over with him, we should have to go back and plough our fields.”

Even while besieging him at Orbetello, they supplied him (GIACOMO PICCININO) with provisions; and he got out of his straits with honor. But at last fate took him. All Italy was betting on the result, when (1465), after a visit with Sforza at Milan, he went to King Ferrante at Naples. In spite of the pledges given, and of his high connections, GIACOMO PICCININO was murdered in the Castel Nuovo.

From the death of GIACOMO PICCININO onwards, the foundations of the new States by the Condottieri became a scandal not to be tolerated. The four great Powers, Naples, Milan, the Papacy, and Venice, formed among themselves a political equilibrium which refused to allow of any disturbance. In the States of the Church, which was swarmed with petty tyrants, who in part were, or had been, Condottieri, the nephews of the Popes, since the time of Sixtus IV, monopolized the right to all such undertakings. But as the first sign of a political crisis, the soldiers of fortune appeared again on the scene.”

Niccolo Machiavelli (May 3, 1469,

June 22, 1527)

Machiavelli has been the greatest source of information that I have found about the lives of Niccolo Piccinino and his sons, Jacopo and Francesco. Machiavelli lived at the time of da Vinci, and recorded much of the history of Italy. He was a celebrated political and military theorist, historian, playwright, diplomat, and military planner. In Niccolo Machiavelli’s book, “History of Florence and the Affairs of Italy”, he describes in detail many of the battles that the Piccinino’s fought in, from the Battle of Anghiari, to their demises. Machiavelli explains in his “Machiavellian” way, the relationships of the states and the Church.

This was indeed an unique period of time. Niccolo Piccinino was born just a few generations after the great Black Plauge that spread throughout Europe. He lived at the dawn of the Renaissance and died 48 years before the discovery of America.

Today in Perugia, Italy there exist the PIAZZA PICCININO in honor of Niccolo. In the Piazza Piccinino there is the spectacular Etruscan well, Pozzo Etrusco, one of the most interesting monuments of that civilization which has only recently been explored and opened to the public. It descends about 115 ft. below road level and is more than 16 ft. wide. The date of construction is much debated, however it is generally thought to have been built about the same-time as the city walls.

On the last Saturday of August, the town of Riva, Italy, traditionally celebrates its “Notte di Fiaba” (Fantasy Night) with music, dazzling lights and spectacular fireworks display over the lake. With this evening, the town commemorates an important historical event. In 1439 Venice and Milan, with whom Riva was allied, were engaged in a bloody war. To attack the troops of Milan from behind, Venice sent a fleet of galleys and other ships from the Adriatic Sea up the Adige River, across Lake Loppio and the San Giovanni Pass to Torbole and Garda. That incredible exploit set the stage for the battle, which took place offshore Maderno on September 29, 1439. The ships of Milan commanded by Nicolo’ Fortebraccio, known as Piccinino, were the victors. To choose a crew to take part in the battle, a contest is held on Fantasy Night between the various neighborhoods of the town in which participants are required to prove their seafaring skills. The team of the winning neighborhood, accompanied to the port by a procession in costume, symbolically boards the galley, carrying flags displaying the emblems of the town.

Erasmo di Narno (Gattamelata)

A condottiere (a soldier of fortune) who served the popes and the republic of Venice, Erasmo was born c. 1370 and served in the wars over Lombardy. He was known for his honesty and is said to have been unusually loyal for a mercenary. Before he entered papal service, he had been captured at Aquilea and escaped through closed mountain passes. Martin V employed him to put down a rebellion in Bologna, and Eugene IV permitted him to leave papal service and fight for Venice. The Venetians were then at war with the Milanese, who were under the command of Niccolò Piccinino, a former comrade. In 1441, Erasmo and his ally, Francesco Sforza (later Duke of Milan), captured Verona, lost it, and recaptured it. After the last battle, Gattamelata suffered two strokes, and although he retained his title, captain general, he never fought again. He retired to Padua, where he died two years later. His memory is preserved in an equestrian statue by Donatello, which was the first grand-scale bronze statue since antiquity.

Bibliography:

Baron, Hans, Crisis of the Early Italian Renaissance

Bergin, T. G., and Speake, J., Encyclopedia of The Renaissance

Burchard, Jakop, The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy

Burke, P., The Italian Renaissance

Clark, Kenneth, Leonardo Da Vinci

Chamberlin, E. R. The World of the Italian Renaissance

Degenhart, A Record of European Armor and Arms

Durant, Will, The Renaissance

Ferguson, W. K., The Renaissance in Historical Thought

Hale, J. R., Renaissance Europe, 1480-1520

A Concise Encyclopedia of the Italian Renaissance

Artist and Warfare in the Renaissance

Encyclopedia Of World Art, McGraw-Hill

Hay, Enys, The Italian Renaissance in Its Historical Background,

Hill, George F., ed., Drawings by Pisanello

Horne, Herbert, The Life of Da Vinci by Giorgio Vasari

Machiavelli, Niccolo, History of Florence and the Affairs of Italy

Rosenberg, C. M., Art and Politics In Early Renaissance Italy